|

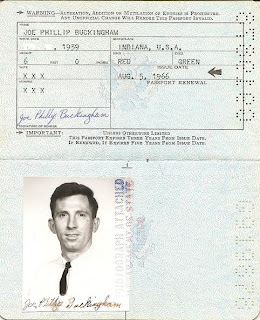

| The passport that was never used. |

A small part of the building was occupied by a roofing firm, but the sheet metal business took up most of the space. The shop was housed in an old building, long and narrow, with a big overhead door at each end. There was an open loft on each side piled high, a segment of it stored sheet metal parts that had been fabricated but not used. The loft was a dust choking place to work on hot summer days, so I was thankful when that particular task came to completion. It took me several weeks to clean and organize the place.

Bill had six or eight journeymen working for him. They were a highly skilled bunch who produced duct work for heating and cooling systems, and also installed them. Most of the contracts were for work done for newly constructed buildings. I liked his crew right away, but I‘m not certain how they looked upon me, a college graduate, ex-teacher, grubbing around in attics, unloading sheet metal, and doing odd jobs. Journeymen went through rigorous training that used a lot of math in design of pieces they make. I was talking math with one of them and he ask me to calculate the square root of a number. I was almost finished when he stopped me and said he just wanted to know if I could really do it.

On one slow day I worked on a safe that sat in the office. It was a big heavy one standing three feet high, but useless because the door could not be shut and the mechanism was jammed. I played around with it, figured what was wrong, got it working, and changed the combination. That impressed everybody, and I was fairly well accepted after that. After all, I could do something practical.

Once I finished the job I expected to be let go, but Graves assigned me to work with Dutch Coady, his father-in-law. The work was more enjoyable after that as I got to go around town with Dutch who ran errands and delivered materials to work sites. Since he was the boss’s son-in-law he had more latitude and many of his errands could be better described as “government jobs”, that’s how he characterized them.

Dutch was an accomplished poker player, a reformed alcoholic, and active in the AA. From him I received advice in card playing and an eye opening introduction to the world of Alcoholics Anonymous. He was a jovial guy who seemed to know half the city residents. We often met people on the street who he would stop and talk to. Upon finishing, as we turned to walk away, he would say, his thumb jerking back toward the individual, “He’s an alcoholic”. “He” might be a lawyer on one occasion or a doctor the next. I began to wonder if half the people in town might not be alcoholics.

I accompanied him to several AA meetings, and when he went on “government jobs”, like taking a bottle to someone on a bender. Once he had me climb a long flight of stairs with him when he delivered booze and cigarettes to a couple in a run down apartment. I remember the guy wore a sweaty T-shirt and the woman stood in her petty coat - both strung out. Dutch said there was no use trying to keep booze from anyone still bent on pursuing the addiction. They were going to drink one way or another, and it was safer to just take a bottle to them. He said they might consider quitting when they hit bottom, but nothing was certain about alcoholism.

Once when were on lunch break, just outside of the café, guy hit us up for money to get something to eat. Dutch invited him in telling him he‘d pop for lunch. The guy made some excuse about having a weak stomach and needed a special diet. To my surprise Dutch turned and headed on to the café. Inside he said, “If the son-of-a-bitch asked for money for a drink I‘d have given in to him“.

I learned something there. Since there was no hunger in America the only people on the streets to ask for money were alcoholics. Offer to buy them a meal. They won’t accept an invitation because they just want a drink. I never dreamed there were people who might really be hungry.

I’ve never been hungry, at least I’ve never known the gnawing emptiness that goes on for days or weeks. Mine was always of the pleasant kind with anticipation of a meal to be forthcoming. I wasn’t aware of anybody being hungry in this country as a cornucopia seemed to lie all around us, but events set me straight on a winter days in January of 1967.

Summer came to an end. Friends gave me a going- away party at which they presented me with a leather passport wallet, which I still have. But my adventure to Europe was postponed due to a war in Vietnam, and the fact that I had a record thirteen deferments granted by the local Draft Board. I made the mistake of asking the board if it was okay if I sailed for Europe. They said no, and I learned that there are times you don’t ask questions, do it and ask later. So in early winter I moved to Chicago to try my fortune in the “Big City”.

Life is faster in a big town. I once read of a study that determined people walked faster in big towns, that their speed of perambulating is directly proportional to the size of the city - the bigger, the faster they walk. I was from a relatively small city and it took a while to adapt, so my pace was slower and I often made eye contact with those coming toward me. I didn’t realize it for a time, but that behavior made me a target. People approached me to ask for money to get something to eat. It happened more often than I would have expected.

Thinking they were just drunks wanting a drink I’d answer as Gus would. If I were close to a restaurant, I’d invite them to a meal. To my surprise too many accepted. Usually I bought them a hotdog or a hamburger, but one old man stands out in my memory. Tall and thin, he was wearing a long overcoat and a mariner’s sock hat, his wrinkled skin as black as ancestors of slave ships not many generations before.

He ask me in front of an upscale cafeteria in the Near North. I told him I wouldn’t give him money, but I’d take him in for a meal. He accepted. We went in and I gave him a tray and told him to go on and pick what he wanted. The man humbly took it and went down the line selecting a healthy amount. I paid and we found a small table for two. I sat opposite him for a short while, now wishing I’d talked to him, but I’ve always been cautiously aware of the fine line that can exist between friendly curiosity and the nosy invasion of a person’s privacy.

I remember he was slathering butter on a bun when I decided it was time to go. I stood and put out my hand to shake his as I said goodbye. He surprised me by grabbing it with both of his and pressing it to his cheek; his eyes closed. It was emotionally moving to experience such gratitude. Embarrassed, I jerked it from his grasp and said, “Don’t do that”. I took my leave and turning away, noticed a woman at the opposite table looking at me with an enigmatic smile.

I became like a big city person after that. I walked fast, kept my eyes trained on the sidewalk and never made eye contact. I couldn’t afford to feed all the people that were hungry.

No comments:

Post a Comment